Intussusception is the commonest cause of acute bowel obstruction in children and if left untreated may progress rapidly to sepsis and patient death.

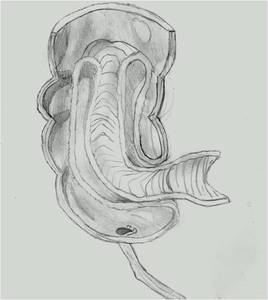

The telescoping of bowel into itself is most eloquently explained by the illustration in Figure 1

Fig. 1: Ileo-colic intussusception: the intussusceptum, here the terminal ileum, invaginates anterogradely into the intussuscepiens, here the caecum/ascending colon

The mechanism of intussusception is thought to be due to hypertrophy of lymphoid tissue in the small bowel wall,

and occasionally pathological lead points are identified.

Pathological lead points are found in 5-10% of cases and include Meckel’s diverticulum,

polyp,

lymphosarcoma,

duplication cyst or Henoch Schoenlein Purpura [1].

Infants classically present with a triad of symptoms- vomiting,

abdominal pain and bloody (occasionally described as resembling redcurrent jelly) stools.

This triad is present in less than 25% of cases[2],

and other common clinical findings include intermittent drawing up of the knees and a palpable lump in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen with an associated right iliac fossa “emptiness”.

Diagnosis is best confirmed on ultrasound,

which has accuracy approaching 100%,

compared with abdominal radiographs which have a sensitivity of 45% and are no longer recommended[3].

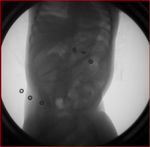

Classic ultrasound findings include a crescent-in-donut or target appearance of the intussusception when viewed in the transverse plain (Figure 2),

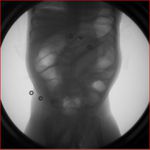

or a hayfork,

pseudokidney,

or sandwich appearance when viewed longditudinally (Figure 3).

Fig. 2: Ultrasound image of an intussusception in a 2 1/2 year old boy, showing a typical tranverse appearance of a target sign.

Fig. 3: Ultrasound image of an intussusception in a 4 month old boy, showing a longditudinal view, often described as a hamburger or a "pseudokidney"

Surgical reduction was popularized by Sir Frederick Treves (1853-1923) who described the condition as “exceedingly fatal” in infants,

with a mortality rate of 70% at the end of the 19th century[4].

Mortality rates have thankfully continued to fall since those early days,

and this reduced mortality has continued into the last century with annual deaths in England and Wales falling from 30 during the 1960s to under 10 per year in the early 1980s[5].

Since the time of Aristotle,

the notion of air insufflation for reduction has been attempted[4],

and more recently,

radiologically observed baro-reduction is one of the primary treatment options for children with this condition. Alternatively,

hydrostatic reduction under ultrasound guidance is performed,

with similar success rates but with the advantage of avoiding administering ionizing radiation to the child.

No consensus exists over which of the two radiologically guided treatments is superior [6].

A recent paper has confirmed that factors contributing to failure of pneumatic reduction have been identified as delayed presentation (symptoms present for more than 24hours),

lethargy and diarrhea as presenting symptoms,

and extent of intussusception[7].

Other clinical and imaging features that are associated with failed radiological reduction include the presence of trapped fluid between the layers of the intussusception,

symptomatic small bowel obstruction,

atypical patient age,

and dehydration [8].

However,

the presence of some,

or indeed all,

of these characteristics are not contra-indications for attempt of radiological reduction- the only contraindications are the presence of free intraperitoneal air,

shock or peritonism.

The Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children is the only dedicated paediatric radiology department in Northern Ireland,

catering for an estimated paediatric population of 357,752 (persons under 15 years of age,

2010) [9]. We aim to audit recent practice at intussusception reduction from April 2007 through June 2012.

Our primary objective was to assess success rates for comparison with RCR standards and secondary aims were to investigate contributory factors in the cases of failed radiological reductions.

We use ultrasound to confirm the presence of intussusception and air enema for reduction.

Figures 4-6 are a series of fluoroscopy images from a successful air enema in our centre during the study period.

Our protocol mandates a senior surgical doctor to be present,

and for the patient to have a functioning intravenous line before the procedure commences.

Parents are briefed on the procedure,

the intended benefits,

potential risks,

and alternatives and verbal or written consent is obtained.

The device used in our institution is a locally fashioned contraption (Figure 7) with a guage to ensure the maximum safe insufflation pressure (120mmHg) is not exceeded.

Fig. 7: Figure 7

The device used to insufflate air for our pneumatic intussusception reductions was built by our local department of medical physics. Air is pumped manually, by squeezing the bulb, and the analogue dial displays the pressure in mmHg

.