As previously explained,

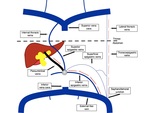

the paraumbilical veins can become dilated and allow blood flow away from the liver (hepatofugal direction) or towards the liver (hepatopetal).

The first being related to PORTAL HYPERTENSION and the second to CHRONIC EXTENSIVE INFERIOR VENA CAVA THROMBOSIS.

We present a series of cases of patent paraumbilical veins found on ultrasound examination divided by mechanism of occurrence and etiology.

PORTAL HYPERTENSION

In this scenario,

the increase of the blood pressure inside the portal system,

notably in the left branch of the portal vein,

forces blood to the patent segment of the umbilical vein (Baumgarten’s recess) and then to subcapsular veins,

finally reaching the paraumbilical veins.

Direct communication between some of the paraumbilical veins and the left branch of the portal system is also possible.

Ultrasound-Doppler evaluation may show the following signs of portal hypertension:

- diameter increase of the main portal venous system components (portal vein and/or branches,

splenic vein,

superior mesenteric vein);

- reduction of the mean velocity of the blood flow in these veins;

- inversion of the direction of the blood flow through these veins;

- thrombosis of the portal vein or other portal venous system components;

- splenomegaly;

- variable volume of ascites;

- establishment of collateral circulation;

- patent paraumbilical veins with hepatofugal flow.

Although one or more paraumbilical veins may become engorged,

the most common finding is of a single patent paraumbilical vein,

that may show a linear course or be tortuous and varicose.

It is important to mention that once the paraumbilical veins are enlarged and patent,

the blood flow through the portal system may show normal velocity,

simulating absence of portal hypertension.

For this reason,

routine search of a patent paraumbilical vein and other main collateral pathways is mandatory in patients at risk for portal hypertension.

The etiology of the portal hypertension can be divided by level related to the liver:

-

pre-hepatic: portal vein thrombosis or compression,

leading to left-sided portal hypertension

-

hepatic: presinusoidal,

sinusoidal and post-sinusoidal

-

Suprahepatic: Budd-Chiari Syndrome and right heart insufficiency.

The most common cause is cirrhosis,

a type of portal hypertension at the hepatic sinusoidal level.

We present a series of cases of the most common causes of portal hypertension in our institution: cirrhosis and Schistosomiasis.

Since both conditions may show similar signs of portal hypertension,

clinical history,

blood markers and B-mode evaluation may help to differentiate them.

We also present a case of Budd-Chiari Syndrome with signs of portal hypertension.

- Cirrhosis

Characterized by impaired functioning of the liver due to long-term damage,

mainly from chronic alcohol abuse,

hepatitis B,

hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Centrilobular fibrosis leads to portal hypertension at the hepatic sinusoidal level.

Besides signs of portal hypertension,

ultrasound B-mode evaluation may show:

-

shrunken liver with nodular surface and coarse heterogeneous echotexture;

-

elevated caudate-lobe ratio;

-

reduction of the IV segment of the liver;

-

moderate to large splenomegaly;

-

variable volume of ascites.

- Hepatosplenic Schistosomiasis

This disease is caused by human infestation by Schistosoma Mansoni.

It is prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas especially in poor communities without access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation.

It basically affects the portal-mesenteric vessels,

thus preserving liver function.

Periportal fibrosis is the cause of portal hypertension in this condition,

at the hepatic presinusoidal level.

Ultrasound B-mode evaluation may show [6]:

-

periportal fibrosis and thickening of the gallbladder wall;

-

reduction of the right lobe of the liver and prominence of the left lobe;

-

the liver surface remains smooth;

-

massive splenomegaly;

-

variable volume of ascites.

- Special condition: Budd-Chiari Syndrome

Patients with chronic Budd-Chiari Syndrome who develop portal hypertension at the suprahepatic level may have patent engorged paraumbilical veins.

Signs and symptoms are abdominal pain,

ascites and enlargement of the liver.

On ultrasound imaging:

- hepatomegaly with heterogeneous echotexture;

- the countours of the liver remain smooth,

unless there is evolution to cirrhosis;

- prominence of the caudate lobe;

- massive ascites;

- thrombosis of hepatic veins and/or inferior vena cava;

- intrahepatic collateral veins [7].

- Ultrasound images

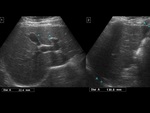

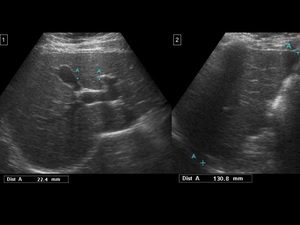

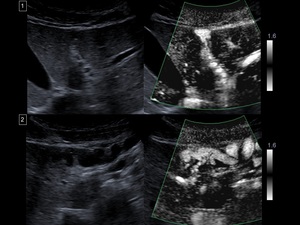

Fig. 12: Patient with alcoholic cirrhosis.

1 and 2) Liver with grossly heterogeneous echotexture, irregular contours and enlargement of the caudate lobe.

3 and 4) Patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow in connection with the left branch of the portal vein.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

Fig. 13: Patient with cirrhosis related to autoimmune hepatitis.

1) Reduction of the segment IV of the liver.

2) Right lobe with regular dimensions and irregular contours.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

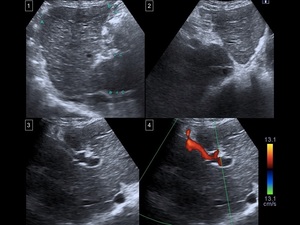

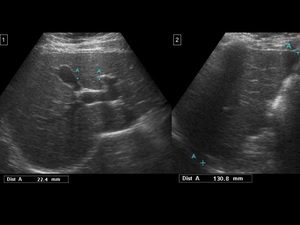

Fig. 14: Patient with cirrhosis.

1) and 2) Patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow.

3) Portal vein with hepatopetal flow and abnormally high velocities.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

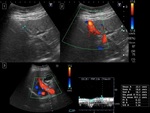

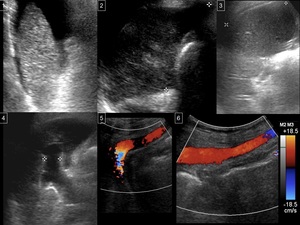

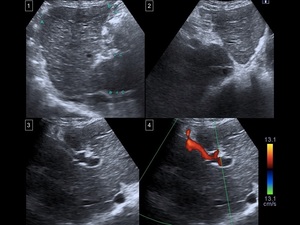

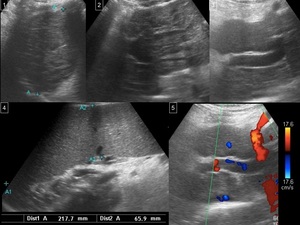

Fig. 15: Cryptogenic cirrhosis.

1) Reduction of the left lobe of the liver.

2) Reduction of the right lobe of the liver.

3) Splenomegaly.

4) Dilated left branch of the portal vein.

5) Patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow, under the left lobe of the liver.

6) Patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow, under the umbilical region.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

- Hepatosplenic Schistosomiasis

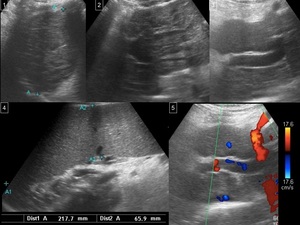

Fig. 16: Patient with Schistosomiasis.

1) Reduced right lobe of the liver.

2) Left lobe and caudate lobe of the liver with regular dimensions.

3) Marked periportal hyperechogenicity, surrounding a very dilated left branch of the portal vein.

4) Massive splenomegaly.

5) Patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

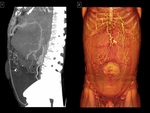

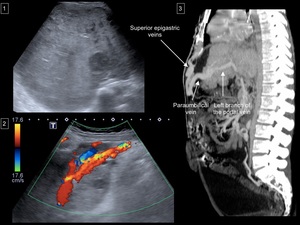

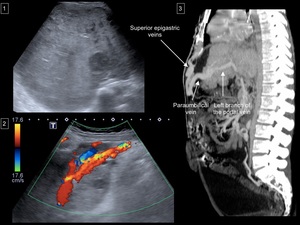

Fig. 17: Budd-Chiari Syndrome due to chronic complete IVC thrombosis in a patient with antithrombin III deficiency (Figs. 17 and 18).

1) Chronic Budd-Chiari Syndrome with signs of cirrhosis.

2) Patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow.

3) Sagittal multiplanar reformation (MPR) image from enhanced CT of the abdomen showing the connection of the paraumbilical vein with the left branch of the portal vein and with the superior epigastric vein, indicating connection of the portal venous system with the internal thoracic veins through the paraumbilical and superior epigastric vein pathway.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

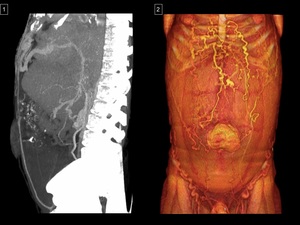

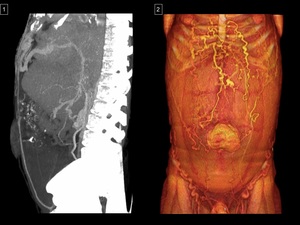

Fig. 18: Budd-Chiari Syndrome due to chronic complete IVC thrombosis in a patient with antithrombin III deficiency (Figs. 17 and 18).

1) Sagittal CT image with Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) from enhanced CT of the abdomen showing the connection of the paraumbilical vein with the left branch of the portal vein and with the superior epigastric vein, indicating connection of the portal venous system with the internal thoracic veins through the paraumbilical and superior epigastric vein pathway.

2) 3D surface-rendered image shows prominent superficial veins on the abdominal wall, mainly at the thoracoabdominal transition.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

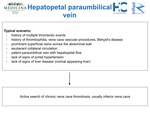

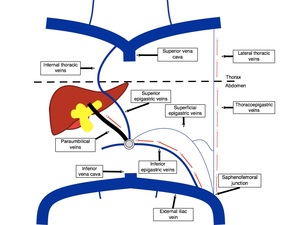

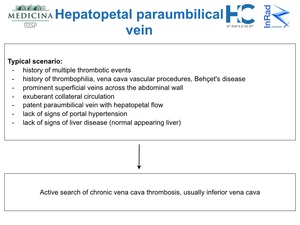

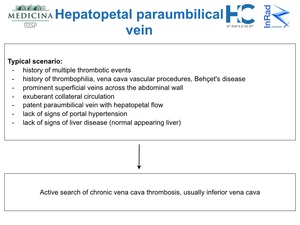

PARAUMBILICAL VEIN WITH HEPATOPETAL FLOW: INFERIOR VENA CAVA THROMBOSIS

A patent paraumbilical vein with hepatopetal flow is very rare and it is usually secondary to extensive chronic inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis [8-10].

If paraumbilical veins with hepatopetal flow are unexpectedly found during ultrasound examination,

we must ask the patient about previous vascular procedures (mainly those involving the inferior vena cava,

directly or not) or history of multiple thrombotic events.

Most cases found in the scientific literature were due to severe thrombophilia and vascular trauma after interventional procedures.

One specific disease was highly associated with this rare situation: Behçet’s disease with extensive vascular manifestation.

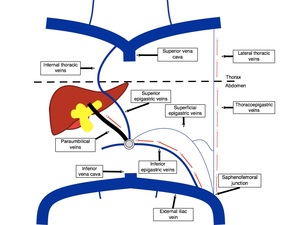

The absence of signs of hepatopathy or portal hypertension and existence of prominent collateral circulation are clues.

Fig. 19: Simplified scheme demonstrating hepatopetal flow in the paraumbilical veins from the inferior epigastric veins in order to bypass chronic inferior vena cava thrombosis. In this situation, blood from the inferior members also uses superficial abdominal veins, retroperitoneal veins and the azygos-hemiazygos pathway to reach the right atrium.

References: José Claudio Nogueira Junqueira, 2018.

Fig. 20: Hepatopetal flow in the paraumbilical vein.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

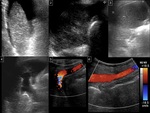

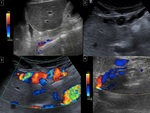

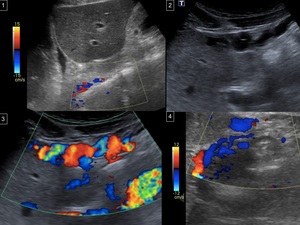

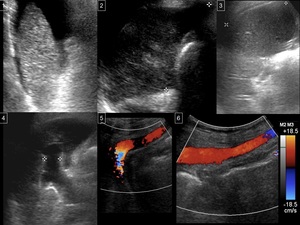

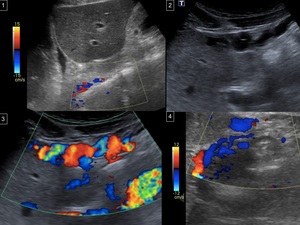

Fig. 21: Behçet's disease (Figs. 21-23).

1) Chronic thrombosis of the IVC, sparing its suprahepatic segment.

2) and 3) Paraumbilical veins on B-mode and color-Doppler images

4) Paraumbilical veins with hepatopetal flow in a sagittal subcostal window on Color-Doppler, connecting with subcapsular venous collaterals and with the left portal vein.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

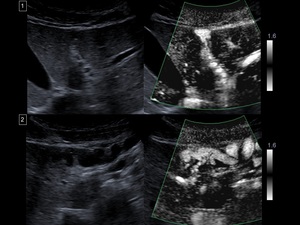

Fig. 22: Behçet's disease (Figs. 21-23).

1) and 2) Communication of the paraumbilical veins with subcapsular venous collaterals and with the left portal vein shown with Superb Microvascular Imaging (SMI)

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

Fig. 23: Behçet's disease (Figs. 21-23).

3D surface-rendered image shows prominent superficial veins parallel the sides of the abdominal wall, suggesting inferior vena cava thrombosis.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.