ETIOLOGY

Considering that a specific cause of the disease has not been objectively established,

the evidence establishes a strong relationship between panniculitis as an autoimmune disorder. In general,

genetic and environmental factors play a fundamental role in the development of autoimmune diseases (6).

Many factors support the hypothesis that PM is an autoimmune disease.

These include the fact that biopsies from the affected regions show chronic inflammation.

In addition,

systemic symptoms that are characteristic of other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease,

which include fever and fatigue,

can occur in patients with PM.

Patients with PM also often have a strong family history of autoimmune diseases.

Finally,

the elevation of inflammatory markers measured in the blood,

such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP),

are often found in patients with PM (6).

Considering that PM occurs in some patients after certain infections (9,10,11),

abdominal surgery or trauma (8),

other theories have been proposed to explain this disorder,

including post-inflammatory reactions to inflammation or acute infection,

or an insufficient blood supply (ischemia) to the mesentery.

(Fig. 2)

Fig. 2: The etiology of PM is not yet clear, however, many theories have been postulated.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The epidemiology of PM has not been fully defined.

A recent study reported that findings compatible with PM occurred in 359 patients (0.24%) of a total of 147,794 MDCT exams performed for more than 5 years in a medical system.

Of these,

100 patients (28%) had known malignancy or later were diagnosed with cancer(7).

In some reports,

the PM has a male predominance of 2:1. And it also appears more frequently during the sixth and seventh decade of life,

and its incidence seems to increase with age.

Children and adolescents are affected less often,

perhaps because of the lower amount of fat in the mesentery.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The symptoms of PM are divided into two categories.

Some symptoms,

such as abdominal pain,

are due to the effect similar to the mass of the mesenteric inflammation and the possible involvement of adjacent structures,

including the small intestine.

The second group of symptoms occurs in the presence of chronic inflammation and may include weight loss,

fever,

and fatigue. Some affected people may develop complications such as small bowel obstruction or acute abdomen.

Small bowel obstruction prevents the passage of food through the intestines and can cause a variety of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms as well as nutrient malabsorption.

In some patients,

a palpable mass can be detected in the middle región of the abdomen mass.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PM is based on the identification of suggestive symptoms,

a detailed history of the patient and an exhaustive evaluation of laboratory markers of inflammation.

For example,

the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and the C-reactive protein (CRP).

The diagnostic methods by images are:

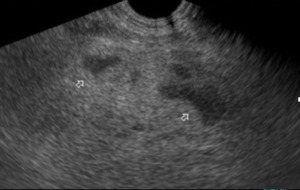

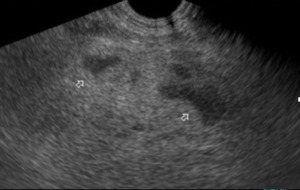

ULTRASONOGRAPHIC study of PM.

The adequate correlation found between the sonographic findings and those of the CT in different studies allows affirming that it is possible to diagnose PM through ultrasound and also to exclude other entities.

Therefore it is important to know some of the main findings (12):

- Mass effect on the mesenteric root of the small intestine,

especially of the jejunum,

manifested by the lack of mesenteric compressibility and the displacement of intestinal loops.

(Fig. 3)

- Homogeneous increase in echogenicity with loss of the normal laminated substructure of the mesentery.

(Fig. 3)

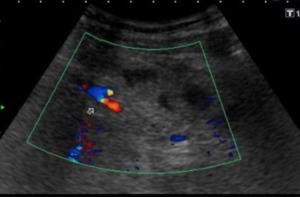

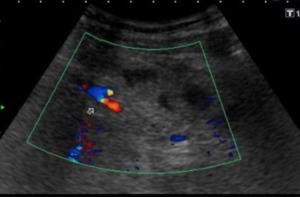

- Enfolding of mesenteric vessels without displacing or stenosing them (Fig. 5)

- Anterior edge of the lesion well defined while the lateral and posterior margins are poorly defined (Fig. 4)

- Upper-abdominal location high or slightly to the left (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: US-Section mesogastrio. There is a diffuse increase in the echogenicity of the mesenteric fat (white arrows), which displaces structures but does not collapse them.

Fig. 4: US Transverse section in epigastrium. Associated with the increase in echogenicity, some ganglionic images smaller than 5mm are recognized

Fig. 5: US Transverse section in mesogastrium. The echogenic mass (PM) involves vascular structures, without affecting their permeability (does not compress them)

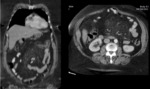

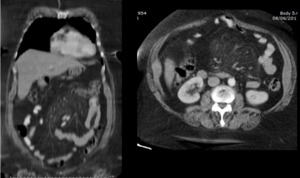

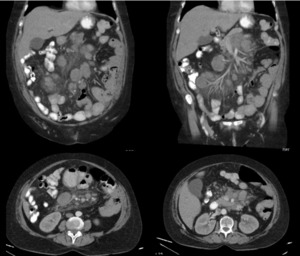

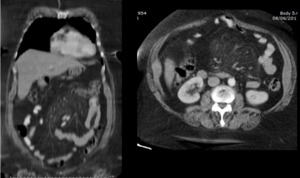

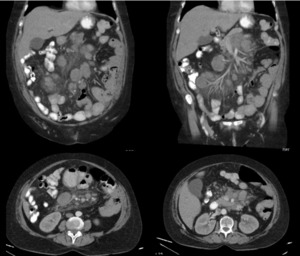

TOMOGRAPHIC findings in mesenteric panniculitis:

PM results in an area similar to the mass of a heterogeneous fat attenuation on CT that can displace local bowel loops but that does not normally displace or compress the surrounding mesenteric vascular structures.

Approximately 90% of the cases involve the mesentery of the small intestine(14),

especially jejunal mesentery (15) located on the left.

- The term "foggy mesentery" was named by Mindelzun et al.

in 1996 (19),

to describe a regional increase in mesenteric fat density that is frequently observed in abdominopelvic CT.

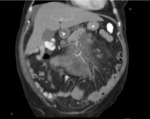

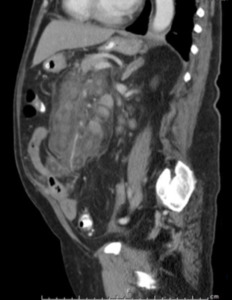

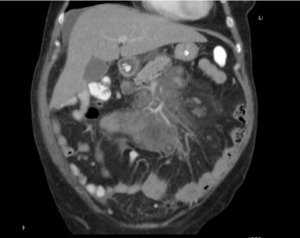

( Fig. 6,

Fig. 7,

Fig. 8).

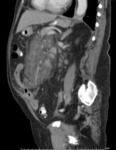

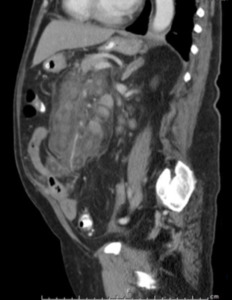

- The sign of the "tumor pseudocapsule": Referred to the presence of a curvilinear peripheral band no greater than 3mm (16) of soft tissue density that limits the heterogeneous mesenteric mass of the surrounding normal mesentery.

It has a sensitivity of close to 50% (17),

but it is important to mention that it can be found in patients with benign and malignant mesentery lipomatous tumors (14).

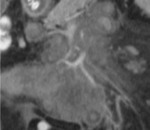

(Fig. 7).

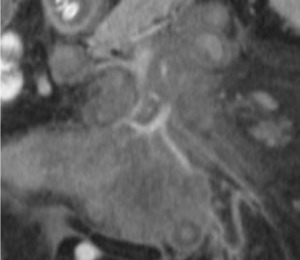

- The "sign of the fatty halo": that refers to the preservation of the density of normal fat in the fatty tissue surrounding the mesenteric vessels.

This sign has a sensitivity of close to 75% (17),

however,

it can be found in patients with mesenteric lymphoma.

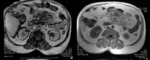

(18) (Fig. 9).

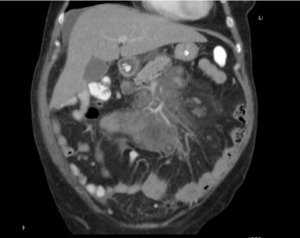

- It is also common to find ganglionic images,

usually less than 5mm,

although it is also possible to find them in some tumoral diseases,

being important for differentiation,

size and reactivity characteristics.

(Fig. 8)

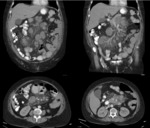

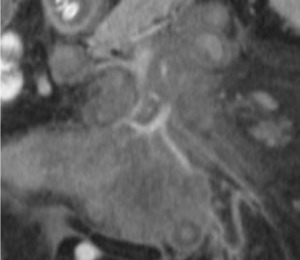

Fig. 6: MDCT. Coronal and axial sections. It is visualized in mesentery projection, slight increase in mesenteric fat cross-linking (Mesentery Mist)

Fig. 7: MDCT. Sagittal section of the abdomen. Heterogeneous mass, in mesenteric root projection, that surrounds structures, without displacing or compressing them, also "pseudocapsule" that defines the pathology.

Fig. 8: MDCT. Coronal section of abdomen. Well defined mass that envelops vascular structures without altering their permeability and some small ganglionic images.

Fig. 9: MDCT. Coronal section abdomen. Presence of the sign of the fatty halo, halo of less attenuation, adjacent to the vessels.

Findings in Retractable Mesenteritis (MR):

MR represents the most chronic and fulminating subgroup of sclerosing mesenteritis (8).

It is characterized by the presence of one or more irregular fibrotic soft tissue mesenteric masses.

Calcifications can be observed within the mass,

as sequential signs of fat necrosis.

There may also be englobement of the adjacent intestinal loops and vascular structures,

which leads to signs of obstruction and sometimes to hollow visceral ischemia (14).

Other diagnostic methods:

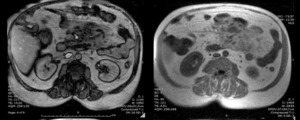

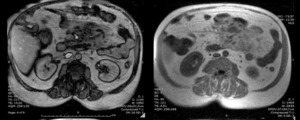

In the MRI,

a mesenteric mass with intermediate signal intensity is observed in the T1-weighted images and with a slightly higher signal intensity in the images enhanced in T2 (13).

(Fig. 10)

Fig. 10: MRI Sequence out of phase and in phase. Hyperintense mass in mesenteric root projection

TREATMENT

There is no standardized medical treatment,

but variable results have been obtained with anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents. Surgical resection should be reserved for symptomatic cases that do not respond to conservative treatment or in cases of intestinal obstruction.

The prognosis is usually good and recurrence is rare (20).

PATHOLOGIES ASSOCIATED WITH PM THAT MAY GENERATE DOUBT IN THE DIAGNOSIS

When a foggy mesentery is observed on CT,

it is the responsibility of the radiologist to consider and,

if possible,

exclude alternative causes of a regional increase in mesenteric fat density,

such as edema,

hemorrhage,

lymphedema,

inflammation,

and neoplasia before suggesting a diagnosis of PM.

(Fig. 11)

Fig. 11: MDCT. Abdomen. A well-defined mass is visualized that surrounds vascular structures without altering their permeability and multiple ganglionic images in the adenomegalic range. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma