The ultrasonography (US) provides valuable information on peritonsillar swelling.

We will describe our ultrasound technique and present some illustrative images from clinical practice.

In our department,

we have been mainly using the transcutaneous ultrasound technique.

Why?

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the neck traditionally has been used to accurately diagnose suspected peritonsillar abscess (PTA).

However,

it is far from ideal.

It is an expensive method,

and there is a growing concern over radiation exposure,

which can lead to an increase rate of cancer especially because peritonsillar abscesses are more common in the younger age population.

CT scan of the neck may also be helpful identifying concomitant spread of infection beyond the peritonsillar space to other neck spaces and evaluating its exact extent.

Magnetic resonance imaging is also being used to diagnose PTA and has the advantages of improved soft tissue detail without the associated radiation risk of a CT.

However,

besides being an expensive imaging modality,

magnetic resonance imaging takes longer and has greater problems of availability when compared with CT scan.

This can lead to longer waiting times,

increasing the risk of complications.

Blind needle aspiration is the typical method of choice to diagnose (and sometimes treat) a PTA.

However,

some studies have found it unreliable with a reported false-negative rate of 10% to 24%.

Many needle aspirations are performed blindly aiming for the point with the maximum bulging and fluctuance – usually in the superior pole of the palatine tonsil (because approximately two thirds of PTAs occur in this region).

If the aspiration is unsuccessful,

further attempts will be conducted typically in the middle and lower poles of the tonsil,

a region where many practitioners hesitate to blindly aspirate purulent collections (especially in the distal part of the tonsil) due to its proximity to the internal carotid artery.

Diagnosis and treatment by needle aspiration can also be extremely difficult in awake children due to its invasive and painful nature.

In addition,

due to the possibility of the abscess being multiloculated and variable in location,

multiple blind aspirations may be attempted,

which would be even more uncomfortable,

painful,

and potentially dangerous.

Instead,

ultrasound,

either intraoral ultrasound or transcutaneous ultrasound,

can provide a reliable ionized radiation-free,

low-cost and real-time imaging alternative and should become the initial imaging modality of choice for evaluation of PTA.

Intraoral ultrasound can also be used for real-time needle guidance and numerous studies support its safety and efficacy.

However,

evaluation of deep extent of disease is limited,

it may be difficult to use in patients with severe trismus due to the size of the intracavitary probe and the procedure may frighten children.

Transcutaneous ultrasound approach is easier technically,

so it takes less time to perform,

and it is less frightening for children.

Additionally,

contrary to the intra-oral approach,

there is no need to use topical anesthetic spray in the posterior pharynx.

How?

Transcutaneous sonography of the tonsils is usually carried out with a high frequency (10-15 MHz) linear probe or curvilinear transducer (6-12 MHz).

The patient is in supine position with the neck extended while scanning.

To start,

we place the transducer under and medial to the angle of the mandible with the probe marker facing the patient’s right side.

Submandibular gland is located first.

Then the transducer is directed posterosuperiorly toward the tonsillar fossa.

The tonsil is found immediately deep to the submandibular gland,

laterally to the tongue and medially to the facial vessels ( Fig. 1 ).

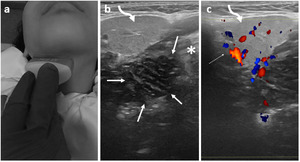

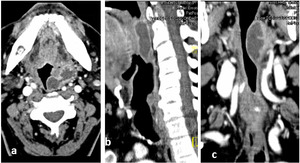

Fig. 1: Tonsillar ultrasound via submandibular approach (right side).

(a) Linear transducer under and medial to the angle of the mandible with the probe marker facing the patient’s right side. (b) Gray-scale and (c) Color Doppler transverse image of the right submandibular region shows the submandibular gland (curved arrow) and in a deeper location the right tonsil (between arrows) which appears as an ovoid, hypoechoic structure.

The soft tissues of the floor of mouth including the tongue (asterisk) are seen medially and the facial vessels are situated laterally (dotted arrow).

If having difficulty visualizing the palatine tonsil,

one can try another approach first by locating the internal jugular vein and carotid artery and then tilting the transducer cephalad,

noting the course of the common,

then internal carotid artery,

with the palatine tonsil appearing medially and,

adjacent to it,

the hyperechoic oropharyngeal space representing foci of air in the pharynx.

There is another possible approach (transverse plane in the midline of the submental region) which allows us to visualize both tonsils at the same time,

something that is useful because it provides a general spatial overview making it easier to compare both sites ( Fig. 2 ).

This approach is easier to perform on children or adults with low tissue depth.

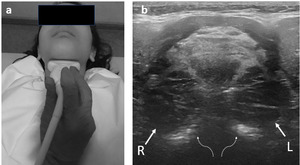

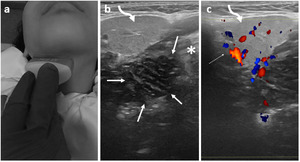

Fig. 2: Tonsillar ultrasound via midline approach. (a) Correct placement of the linear transducer in the midline approach with the neck fully extended. (b) Midline gray-scale transverse image showing right (R) and left (L) tonsils, both with normal size and texture.

Note the hyperechoic oropharyngeal space representing foci of air in the pharynx (dotted curved arrow).

Using colour Doppler can help identify vascular flow from the internal carotid artery,

facial artery and vein as well as hyperemia in inflamed tonsillar parenchyma or lack of intrinsic vascularity in focal fluid collections.

Another important step should be measuring the tonsillar size in a minimum of two planes.

Regional lymph node evaluation is also performed.

What to look for?

Normal tonsil

At ultrasound,

the normal palatine tonsil appears as a small (usually < 20 mm) well-defined,

triangular or ovoid structure with a homogeneous low-level echogenic texture,

with discrete lobulated margins.

There are no studies showing normal tonsil volume,

however a longitudinal length up to 2-2,5 cm can usually be considered normal.

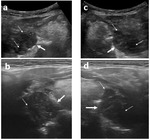

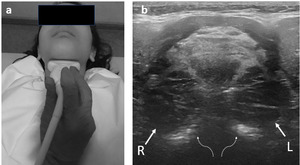

The tonsillar parenchyma has a striated appearance with alternating linear hyperechoic and hypoechoic bands due to the tonsillar crypts ( Fig. 3 ).

Often,

when pressure is applied by the ultrasound transducer,

mobile,

moving echo reflections can be seen along the oropharyngeal space adjacent to the tonsil,

representing foci of air in the pharynx.

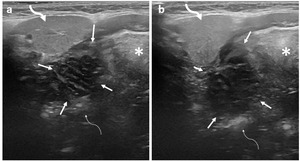

Fig. 3: (a) and (b) show two normal right tonsils (between arrows) located deep to the ipsilateral submandibular gland (curved arrow) clearly presenting the typical striated structure of tonsillar parenchyma.

Note the right half of the tongue (asterisk) located medial to the tonsil and the hyperechoic oropharyngeal space representing foci of air in the pharynx (dotted curved arrow).

The most common benign or pathological findings are listed below:

- Tonsillar hyperplasia/hypertrophy: Symmetrical,

homogeneous enlargement of both tonsils,

measuring up to 4 cm,

in the absence of acute symptomatology;

- Uncomplicated tonsillitis; Inflammation of the tonsil,

either bacterial or viral.

It manifests as tonsillar hypertrophy without fluid collection,

in the presence of acute symptoms.

At ultrasound,

the affected tonsil shows increase in size greater than 2 cm in at least one dimension,

with preserved homogeneous,

hypoechogenic echotexture ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4: Uncomplicated tonsillitis in a 15-year old boy with a history of recent sore throat and odynophagia. This gray-scale image shows an enlarged right tonsil (between arrows) measuring 31 mm. Note preserved striated appearance of the tonsillar parenchyma suggesting uncomplicated tonsillitis. The left tonsil (not shown) was also moderately enlarged measuring 29 mm.

Note the right half of the tongue (asterisk) located medial to the tonsil.

Both tonsillar hypertrophy and uncomplicated tonsillitis may show the typical tonsillar striated appearance.

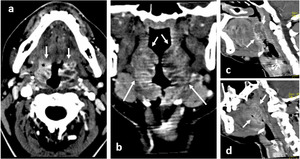

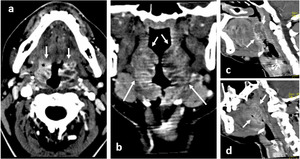

In CT evaluation it is also possible to visualize a striated pattern of internal enhancement (tiger stripe sign) relatively specific for nonsuppurative tonsillitis ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5: Nonsuppurative tonsillitis in a 29-year old woman with fever and a history of recent sore throat and odynophagia. (a) Axial and (b) coronal contrast enhanced CT scan of the neck shows the typical striated appearance (tiger stripe sign) of the bilaterally enlarged tonsils (arrows), consistent with nonsuppurative tonsillitis. These findings are also seen in (c) sagittal view of the left tonsil and (d) sagittal view of the right tonsil.

Note the small areas of heterogeneity in both tonsils, consistent with edema, but without frank abscess.

- Peritonsillar cellulitis or,

as some authors refer,

peritonsillar phlegmon: Represents an inflammation of the tissue between the tonsillar capsule and the pharyngeal muscles but without a purulent collection,

therefore does not benefit from drainage intervention.

May be considered as an intermediate state between uncomplicated tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess.

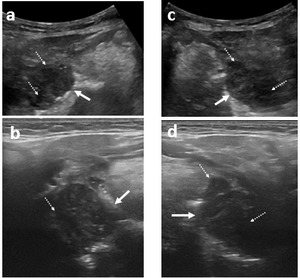

At ultrasound,

tonsil usually appears enlarged with heterogeneous parenchyma associated with perifocal increased echogenicity,

in keeping with marked surrounding soft-tissue edema.

Sometimes,

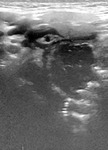

it may show small ill-defined internal hypoechoic areas that may represent developing areas of edema or necrosis or initial stage of purulence without a well-defined abscess ( Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 ).

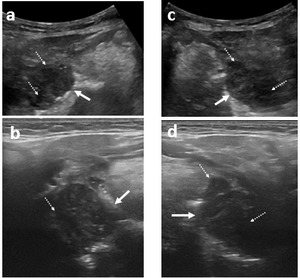

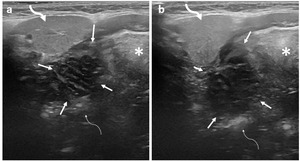

Fig. 6: Peritonsillar cellulitis in a 17-year-old girl with two days of odynophagia, fever and mild trismus. Gray scale image using (a) convex transducer and (b) linear transducer shows an enlarged right tonsil (arrows) measuring 32 mm. Gray scale imaging using (c) convex transducer and (d) linear transducer also shows an enlarged left tonsil (arrows) measuring 38 mm.

Both tonsils show parenchymal heterogeneity with scattered small hypoechoic areas (dotted arrows) which may correspond to areas of developing edema or purulence as no pus was obtained on needle drainage. There is a slight increase in the echogenicity of surrounding peritonsillar tissue. The patient improved with antibiotics.

Fig. 7: Peritonsillar cellulitis in a 27-year-old man with 5 days history of odynophagia, decreased oral intake and mild trismus. Gray scale image of the right tonsillar fossa shows a slightly enlarged tonsil measuring 28 mm with parenchymal heterogeneity and markedly increased echogenicity of surrounding tissues compatible with perifocal edema/inflammation.

At CT,

the lesion may appear as an ill-defined low-density collection that does not show a peripheral rim of enhancement or thickened walls.

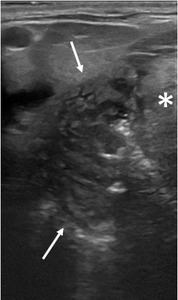

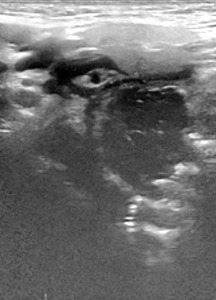

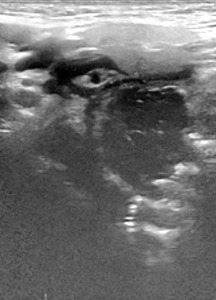

- Intratonsillar abscess: It is a rare condition,

characterized by formation of an abscess/collection of pus within tonsillar parenchyma.

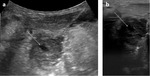

The small intratonsillar liquefaction may be identified as an avascular area or,

if there is gas within the formation,

by the presence hyperechoic foci ( Fig. 8 ).

It is important to promptly diagnose this entity,

as these abscesses can be successfully treated with intratonsillar needle drainage and intravenous antibiotics,

with rapid resolution of symptoms.

Fig. 8: Intratonsillar abscesses in a 15-year-old boy with odynophagia, reduced oral intake and fever. Gray scale imaging using (a) convex transducer and (b) linear transducer shows an enlarged right tonsil (arrows) with ill-defined contours standing out a central markedly hypoechoic/virtually anechoic area within tonsillar parenchyma that may correspond to pus or necrosis. There is also hyperechogenicity of the surrounding peritonsillar tissues in keeping with inflammatory changes.

This patient improved with drainage and antibiotics.

- Peritonsillar abscess: Characterized by a collection of pus between the palatine tonsillar capsule medially and the pharyngeal muscles laterally.

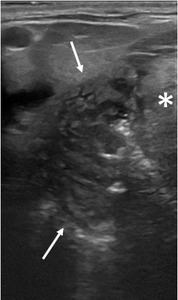

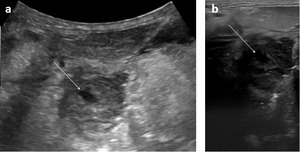

At ultrasound,

it appears as a well-circumscribed hypoechoic or anechoic fluid-filled cavity with irregular margins usually located posterolateral to the palatine tonsil ( Fig. 9 ).

Beware the proximity of the internal carotid artery and the facial artery to the peritonsillar abscess when to avoid laceration of these arteries during drainage.

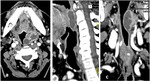

Fig. 9: Peritonsillar abscesses in a 73-year-old man with fever, throat pain and marked trismus. On clinical exam, deviation of uvula to the right could be seen.

Gray scale imaging using (a) convex transducer and (b) linear transducer shows an enlarged left tonsil and an irregular anechoic area along its lateral aspect, compatible with peritonsillar abscess (dotted arrow in a; outlined in b).

Ultrasound study (intra-oral approach also tried but not shown) could not clearly rule out spread to parapharyngeal space so a CT was ordered (Fig. 10).

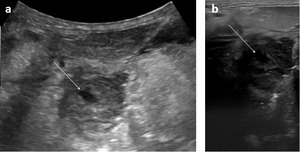

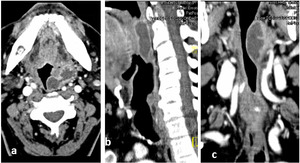

- Parapharyngeal abscess: Characterized by purulent spread of inflammation within the parapharyngeal space,

that may arise from the tonsils.

In these cases,

additional imaging by CT with multiplanar views should be considered to evaluate extent.

CT may show increased parapharyngeal fat density that respects the cervical fasciae.

inhomogeneous uni- or multilocular fluid or gas collection showing peripheral enhancement after contrast administration and perifocal edema ( Fig. 10 ).

Fig. 10: Left peritonsillar abscess with concomitant spread to adjacent pharyngeal space forming a communication with parapharyngeal abscess. Same patient as fig. 9.

(a) Axial contrast-enhanced showing a left peritonsillar abscess connecting with a parapharyngeal abscess, associated with increased surrounding fat density compatible with inflammatory changes.

The full extent of the parapharyngeal abscess can be assessed with the (b) coronal and (c) sagittal views. Note the reduction of the airway calibre.