A. Review of the Anatomy of Cervical Esophagus

1.Anatomical segmentation of cervical esophagus

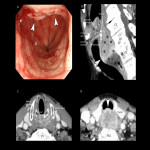

The upper end of the cervical esophagus is the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), and the lower end is the sternal notch according to AJCC 8th/UICC 8th [2,3] (Fig 1). The location is defined as the cervical esophageal cancer if the epicenter of the tumor begins within the UES and sternal notch.

2.Transition from the hypopharynx to the cervical esophagus

The upper part of the cervical esophagus is continuous with the hypopharynx. The lower part of hypopharynx has a flat shape that extends from side to side, but is narrowed by UES and changes to oval shape of the cervical esophagus (Fig 2). The recognition of this change in shape is useful in identifying the extent of craniocaudal extension of the lesion in transverse images.

3.Imaging anatomy of the cervical esophagus

Imaging anatomy of the cervical esophagus on CT, EUS, and MRI should be familiarized in oncologic practice. Each modality has a different histological resolution and different roles in clinical practice.

- Imaging anatomy with EUS (Fig 3)

EUS is the best method for visualization of the esophageal wall and lymph nodes (LNs) near the esophagus , but it can be an invasive examination if the lesion is located near the esophageal inlet.

In cervical esophageal cancer practice, EUS is more suitable for the evaluation in early stages and lymph node metastasis (LNM) in the lower part of the cervical esophagus.

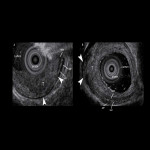

- Imaging anatomy with CT (Fig 4)

Contrast-enhanced CT can discriminate wall structures, although the ability to discriminate wall structures is reduced around the esophageal inlet [4]. CT is a powerful tool to depict the relationship with surrounding structures and is especially important in the cervical esophagus.

- Imaging anatomy with MRI (Fig 5)

It is considered to have the same diagnostic accuracy as CT because of its superior ability to depict the relationship with surrounding tissues [4,5]. On the other hand, the ability to discriminate wall structures is low owing to motion artifacts [5,6].

4.Lymphatic pathway of cervical esophagus

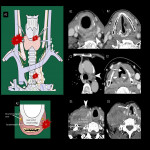

In addition to the general knowledge of the lymphatic flow pathways of the esophagus [7,8] (Fig 6), the following points are characteristic of the cervical esophagus (Fig 7):

- Lateral lymphatics is common, especially in the right recurrent laryngeal nerve node [9,10]

- Lymphatics descending below the aortic arch are less common[7,8]

- Note the lymphatics associated with the retropharynx and anterior neck regions (Fig 7).

5.Anatomy of vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerve

It is essential to be familiar with the related anatomy of these nerves to preserve laryngeal function (Fig 8). Symptoms of laryngeal paralysis and endoscopic evaluation are more diagnostic in clinical practice; subsequently, CT plays a role in depicting an overview.

B. Imaging Findings for Treatment Strategy

Treatment plans are based on the assessment of the progress of the cancer, along with the patient’s general condition and intentions.

The TNM classification for this presentation is based on the AJCC 8th / UICC 8th [2,3] (Fig 9).

1.T category

- T1-3

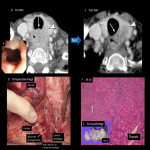

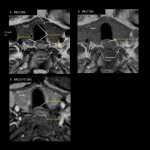

The distinction between T1-3 is mainly performed by conventional and magnifying endoscopy. EUS is considered as an option when the invasion is deeper than the submucosa or the paraesophageal lymph node evaluation is necessary [11,12] (Fig 10-14). Subclassification for superficial esophageal cancer (T1) is based on the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer 11th edition [13] (Fig 10).

When endoscopic evaluation is difficult due to stenosis, CT and MRI are used to evaluate the invasion of adjacent vital organs (Fig 14).

In the cervical esophagus, important organs are closely placed in a small area; therefore, it is often difficult to evalute the cancer staging as T3 or T4 (Fig 14, 16).

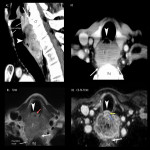

- T4a-b

The absence of the serous membrane allows easy invasion of the surrounding organs in esophageal cancer.

T4 is subcategorized to:

- T4a invading the thyroid (Fig 15)

- T4b invading the trachea, great vessels (subclavian artery, common carotid artery), vertebrae, and prevertebral muscle (Fig 16, 17)

T4b is generally inoperable; however, tracheal invasion can be performed if a permanent tracheal stoma can be placed safely.

Notes on diagnostic imaging:

- Suspect infiltration if the target organ is surrounded by more than half the circumference and the loss of intervening adipose tissue between the tumor and the target on CT.

- Special attention should be paid to the target organ in the epicenter direction of the tumor.

- Knowledge required for laryngeal preservation

The standard treatment for locally advanced CeEC has not yet been established, and laryngeal preservation through cervical esophagectomy or non-surgical treatment (such as CRT) have been developed for CeEC to preserve laryngeal function [15,16](Fig 15, 24).

Requirements for laryngeal preservation surgery include the following:

- Locally advanced cancer other than T4b.

- No infiltration of the larynx, posterior cricoid, vagus, or recurrent laryngeal nerve (Fig 18).

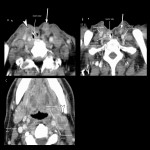

2.N category

Regional LNs for all locations in the esophagus extend from the periesophageal cervical nodes to the celiac nodes by UICC 8th. Other LNMs, such as supraclavicular and jugular LNM, are classified as M1 (Fig 19).

Clinical considerations about LNM in cervical esophageal cancer (Fig 19):

- Lamina propria has a lymphatic network and is prone to LNM, even in superficial carcinomas [17].

- The higher incidence of retrograde LNM of the deep internal neck region due to the cervical and paraoesophagotracheal lymphatics is often continuous [8], especially when extending to the hypopharynx.

- The frequency of lymph node metastasis below the aortic arch is significantly low due to physiological narrowing of the aortic arch [7,18], but not in the case of extension to the upper thoracic esophagus.

Rare but cautionary LNMs include the retropharyngeal and anterior neck regions (Fig 20).

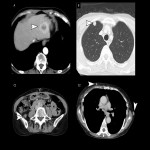

3.M category

Distant metastases are present in 20–30% of esophageal cancer patients at the time of initial diagnosis and are most commonly diagnosed in the liver (35%), lung (20%), bone (9%), and adrenal gland (5%) [19] (Fig 21), because of the submucosal lymphatic network and thoracic duct may be contiguous (43% of autopsies) [20].

CT and positron emission tomography (PET) are usually used for evaluation, but if the lesion is solitary and/or cannot be compared with previous images, it is difficult to make a decision, and a biopsy should be performed.

C. Recurrent pattern and post-treatment complications of cervical esophageal carcinoma

1.Postoperative recurrent pattern of cervical esophageal carcinoma

Long-term survival is possible with early detection and treatment. Recurrence within two years is common after endoscopic treatment, surgery, or definitive chemoradiation.

- Anastomotic (Fig 22) and surgical site recurrence are typical (Fig 23).

- Lymph node recurrence is more likely to occur at sites associated with pretreatment lesions (Fig 22).

- Primary gastric cancer in esophageal gastric grafts is increasing due to improved life expectancy in resected patients [21] (Fig 24).

2.Post-treatment complications

Post-treatment complications are often life-threatening, and familiarity with imaging is required. In addition to treatment complications, the patterns of locoregional recurrence are also described [22,23].

- Anastomotic dehiscence in the early post-operative period (Fig 25)

- Esophageal perforation after CRT (Fig 26)

- Pyogenic spondylitis may occur after treatment in the late stage (Fig 27).

- Postoperative cervical chylorrhea due to thoracic duct injury (Fig 28).

![Fig 10: Subclassification of superficial esophageal cancer (T1) by Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer 11th edition. The endoscopic and EUS evaluations were divided into the following three groups based on the frequency of lymph node metastasis: cT1a-EP/LPM, cT1a-MM/SM1, and pT1b-SM2/SM3 [14].](https://epos.myesr.org/posterimage/esr/ecr2022/160262/media/915520?maxheight=150&maxwidth=150)