The most common symptom is low abdominal pain, followed by nausea with or without vomiting. Less common but not infrequent symptoms and signs include referred pain in the flank, shoulder, or groin, and leukocytosis and fever.

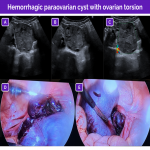

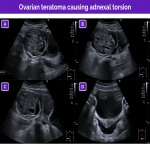

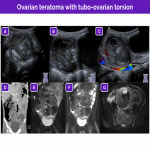

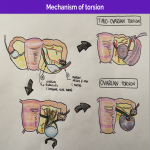

Adnexal torsion can be classified according to its etiology as idiopathic (probably due to ligamentous laxity) or as secondary to an ovarian or extraovarian mass. In premenarche, idiopathic torsion is more common; in adolescents, torsion is often secondary to a mass. The most common ovarian masses are mature cystic teratoma and simple ovarian cysts. The most common extraovarian masses that can result in torsion are paraovarian cysts and paratubal cysts.

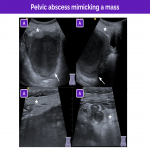

Pelvic ultrasonography is the technique of choice for the initial evaluation of abdominal pain. The ovaries are typically seen lateral and slightly posterior to the uterus in the transverse ultrasound plane. The ovaries are best located by using the bladder as an acoustic window, so it is important to ensure that the bladder is half full/full.

The suprapubic region should be scanned from top to bottom, taking into account that in newborn and young girls the ovaries might be found in the abdomen above the pelvis. Sometimes the left ovary is more difficult to identify due to the interposition of air or feces in the sigma.

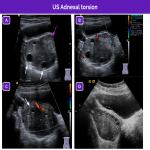

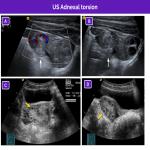

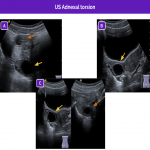

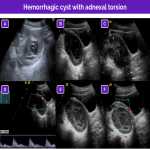

The main ultrasound findings for idiopathic adnexal (ovarian or tubo-ovarian) torsion are resumed in the next figures:

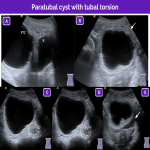

Nevertheless, in certain situations the findings can differ; these situations include isolated tubal torsion and isolated torsion of a paraovarian or paratubal cyst.

Gynecologic entities

Polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome

In ultrasonography, ovaries are considered polycystic when they are both enlarged, spherical, and have more follicles than usual (2‒9 mm in diameter). Some follicles may be peripheral, giving rise to the “string of pearls” sign. However, without accompanying acute pelvic pain.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is characterized by the clinical triad of oligomenorrhea, hirsutism, and obesity.

Like any condition that results in increased ovarian volume, polycystic ovaries entail an increased risk of adnexal torsion.

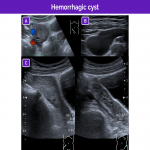

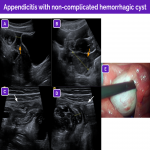

Hemorrhagic cyst

Hemorrhagic cysts usually arise from bleeding into functional cysts (corpus luteum cysts or follicular cysts) in postmenarchal girls; they usually cause abdominal pain. Their appearance on ultrasound varies with the time elapsed from the bleeding event.

Multiple appearances are possible:

- A cystic lesion with normal and/or thickened walls with fluid-fluid levels and/or internal echoes.

- An avascular, solid-appearing mural nodule compatible with a retractile clot. This appearance can be differentiated from a tumor nodule because it has concave external margins and no color Doppler signal. In uncertain cases, it is useful to consider the evolution of the lesion on successive ultrasound studies.

- A solid-appearing hyperechogenic lesion with no Doppler flow that can show posterior acoustic enhancement.

- In the subacute phase, the cystic lesion will have a reticular appearance with internal echoes and multiple fine, avascular septa, due to strands of fibrin.

Hemorrhagic cysts are usually accompanied by free intraperitoneal fluid. Rupture leads to hemoperitoneum, which can be echogenic on ultrasonography.

For these reasons, in the context of acute pain, hemorrhagic cysts are considered the great mimicker of adnexal torsion. On visualizing a heterogeneous, solid-appearing ovarian mass without internal Doppler flow, radiologists should always consider a hemorrhagic cyst.

Importantly, however, hemorrhagic cysts can be complicated with adnexal torsion.

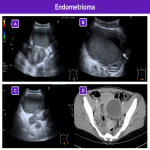

Endometrioma

Endometriomas are ectopic functional endometrial tissue located in the ovary. The main differential diagnosis are hemorrhagic ovarian cysts. Endometriomas are very uncommon in children, but should be taken into consideration in adolescents.

The clinical presentation of endometriomas with acute bleeding or rupture can be similar to that of adnexal torsion. On ultrasonography, these lesions appear as complex unilocular or multilocular cysts with homogeneous low-intensity echoes inside, giving them a ground-glass appearance, as well as fluid-fluid levels. No Doppler signal is seen inside. Unlike hemorrhagic cysts, endometriomas do not resolve over time, and they are normally associated with symptoms in every menstrual cycle.

Adnexal masses

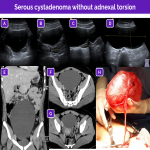

The most common entities that can simulate adnexal torsion are the lesions that predispose patients to torsion, in particular adnexal masses, especially when they are larger than 4cm.

Adnexal masses can be divided into ovarian masses and extra-ovarian masses:

- Ovarian masses increase the overall volume and weight of the ovary, increasing the force on the ligaments that hold it in place. Ovarian masses are usually neoplasms or hemorrhagic cysts; mature cystic teratomas are the most common ovarian tumors.

- Extraovarian masses arise from remnants of the wolffian ducts in the broad ligament or mesosalpinx; they are usually simple cysts.

In general, adnexal masses are asymptomatic, causing symptoms only when complications occur. Thus, in a patient with intense low abdominal pain, a large (>5 cm) mass on imaging should raise suspicion of adnexal torsion.

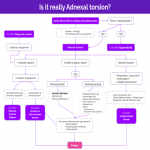

It is equally important to identify signs that rule out adnexal torsion to enable the option of conservative management when possible. Some pitfalls that must be taken into account are:

- Areas of stromal edema or bleeding can be seen as central hypoechoic areas with no Doppler signal. As infarction and necrosis progress, the ovary can become markedly heterogeneous; this appearance can be interpreted as the reticular pattern of a hemorrhagic cyst. If these changes are observed in conjunction with normal ovarian parenchyma, torsion is unlikely.

- Some solid tumors are seen as large masses with no Doppler signal and have cystic changes within them that mimic follicular cysts. Unlike this, these tumors have slightly irregular follicular cysts in a central rather than peripheral location and do not have hyperechogenic margins.

Nevertheless, in the clinical context of acute pelvic pain, these cases are challenging and additional invasive diagnostic procedures are often inevitable.

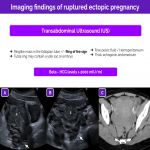

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

Although uncommon in pediatric patients, a ruptured ectopic pregnancy must be taken into account in the differential diagnosis in sexually active adolescents with acute low abdominal pain 5 to 6 weeks after their last menstrual period, sometimes in association with vaginal bleeding.

The most common finding is hemoperitoneum, which can be seen on ultrasonography as echogenic free fluid or clots/bands of fibrin in the peritoneum. The main differential diagnosis is with a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst. It is essential to test for pregnancy or monitor beta-HCG levels.

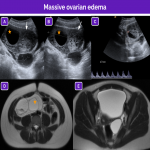

Massive ovarian edema

Massive ovarian edema is a rare mimicker of adnexal torsion that can occur in young women and girls after the age of 6. This entity courses with intermittent pelvic pain over a period of months.

The diffuse stromal edema in the parenchyma is thought to arise from recurrent episodes of twisting and untwisting causing venous and lymphatic compromise without progressing to ischemia and infarction.

On ultrasonography, massive ovarian edema is seen as marked enlargement of the ovary due to hypoechoic, hypovascular stroma that simulates a solid mass. The follicles may be arranged peripherally.

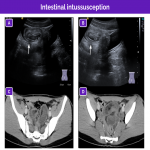

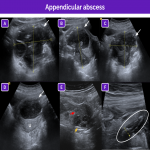

Non-gynecologic entities

Although the workup for abdominal pain in female patients is centered on more common causes such as gastrointestinal entities (appendicitis, enterocolitis, bowel ischemia, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, or intussusception) and genitourinary entities, adnexal torsion must always be included in the differential diagnosis.

Given the wide differential diagnosis, we propose a practical algorithm for correlating the clinical and imaging findings to facilitate the final diagnosis.