Anatomy of the Prostate Gland

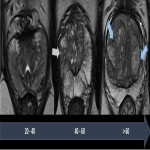

The prostate gland can be divided into three zones with distinct embryologic origins.

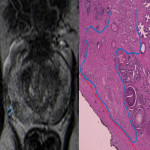

The peripheral zone (PZ) is the largest part of the prostatic gland in young adults. It is deficient anteriorly, in continuity with the anterior fibromuscular stroma. The PZ has a cup-like shape and can be distinguished on T2-weighted images by its high-signal intensity (greater than adjacent fat). On T1-weighted images, it has a homogeneous intermediate signal.

The central zone (CZ) makes up about 25% of the prostatic gland volume. It contains the ejaculatory ducts and lies posteriorly to the urethra on the base of the prostate. The transition zone (TZ) is a small part of the prostatic gland in young adults, comprising about 5% of the prostatic volume. Both CZ and TZ have a homogeneous intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images, almost indistinguishable from the PZ on these sequences. On T2-weighted images, they have a lower signal intensity than the peripheral zone.

The prostatic morphologic changes that occur with age can be seen in Fig 1.

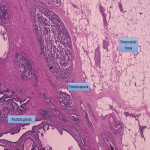

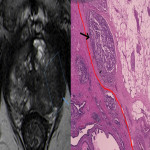

The prostate gland is not delimitated by a true capsule, but by a pseudocapsule, consisting of fibromuscular tissue. It is arranged into three fascia layers which are sparser anteriorly and in the apex. It is depicted on T2-weighted images as a thin, low signal intensity rim that contours the prostate gland. The anterior fibromuscular stroma demonstrates low signal intensity in both T2 and T1-weighted images. (1)

The neurovascular bundles are an important landmark for surgery and there are several anatomic variants regarding its location. However, they are typically located posterior and laterally at 5 and 7 o’clock, at a distance of about 3 mm from the capsule, branching to the apex and base.

In the periprostatic tissue (Fig. 2), we can also find adipose tissue, other small blood vessels, lymphatics, the periprostatic fascia, the posterior prostatic fascia and seminal vesicles fascia (Denonvillers) and other structural ligaments that hold the prostate. (2)

Extra-capsular Extension - MRI

The staging of PCa is determining in the treatment choice, as different options are available whether the disease is organ-confined or is local or distant disseminated. Locally advanced disease refers to ECE, seminal vesicle invasion or involvement of other pelvic structures. (3)

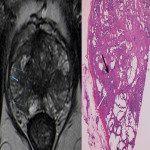

Despite its high specificity, MRI has lower sensitivity in the detection of ECE. (4) The detection of ECE on MRI currently relies on the visualization of its subjective findings, secondary to macroscopic extension and its mechanical consequences. (5) These findings are different according to the aggressivity of the tumor and the degree of ECE. On MRI, features that suggest ECE can be divided into early and late findings of ECE (Figs. 3 and 4). These criteria are based on a chronological concept of cancer growth from truly intraprostatic to truly extraprostatic, in accordance with established histopathologic criteria for ECE.

The early findings are:

- broad tumor contact with the prostate capsule;

- smooth capsular buldging (smooth projection over the prostatic margin);

- capsular disruption (defined as a discontinuity in the low signal prostatic margin).

As the tumor grows under the capsule, tumoral glands form perceptible deposits that can be seen on MRI as late findings, which include:

- irregular contour (loss of the clear interface with the periprostatic fat);

- obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle (disappearance of the angle formed by the rectum and the prostate gland);

- periprostatic fat infiltration (replacement of the fat high-signal intensity by low-signal intensity);

- presence of measurable tumor in the periprostatic fat (presence of an obvious tissue in the periprostatic space).

The late findings have a higher predictive positive value for EPE and its assessment has a higher reproducibility since they are more conspicuous than the early findings. (6)

Regarding the neurovascular bundle invasion (NVBI), it can be suggested on MRI by the presence of neurovascular bundle asymmetry or by detecting direct tumoral extension (Fig. 5).

Extra-capsular Extension – Pathology (pECE)

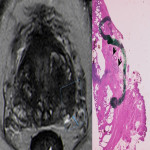

At pathology, the evaluation of pECE can be challenging, as the prostate lacks a true capsule and its boundaries are not easily defined, especially at the level of the apex and at the anterior aspect of the gland. The pseudocapsule consists of organized layers of condensed smooth muscle (Fig. 6) that may be intermixed with the prostatic stroma and, thus, may be hard to be correctly delineated. (2)

At the apex, the prostatic tissue is mixed with skeletal muscle from the urogenital diaphragm but, if tumoral cells are seen within skeletal muscle, it does not necessarily mean ECE. According to the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus (7), there are no definitive criteria to define ECE at the prostatic apex.

Likewise, at the anterior part, the prostatic boundaries are also imprecise, with glandular stroma admixed with fibromuscular tissue from the urogenital diaphragm. However, at that level, ECE is defined by the presence of tumoral glands outside the contour of the normal prostatic tissue. (7)

The diagnosis of pECE implies the presence of one of the following criteria:

- neoplastic cells are seen in the periprostatic fat;

- if tumoral glands are seen surrounding the nerves in the neurovascular bundles;

- if there is a tumoral extension beyond the periphery of the prostate.

The degree of ECE can be then divided into focal or extensive. Focal extension is present if the tumoral glands do not occupy more than one high-power field on no more than two separate histopathological sections, whereas it is defined as extensive if the extension is superior to the stated. (8)

Radiologic-pathologic correlation