1. RECTUM: DO WE ALL UNDERSTAND THE SAME THING?

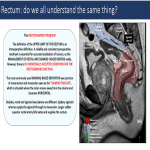

The definition of the rectum is not without debate and varies according to medical speciality (Figure 1).

The rectum is located between the sigma and the anal canal. In general, the most useful landmark for the transition from the sigmoid colon to the rectum is the loss of the taenia coli, the appendices epiploicae and the surgical mesocolon at about the level of the third sacral vertebra at the rectosigmoid junction, where the superior rectal artery and the hypogastric nerves enter the pelvic cavity. The transition from the rectum to the anal canal is marked by the dentate line and is surgically placed at the level of the levator ani muscle. The most commonly employed definition of the rectum is 15 cm from the anal verge.

Imaging allows a non-invasively assessment of main anatomical landmarks to define the rectum (Figure 2-3).

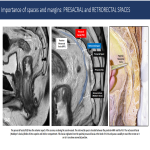

2. IMPORTANCE OF SPACES AND MARGINS

a) Mesorectum

The mesorectal fascia (visceral layer of the endopelvic fascia) encircles the rectum and the mesorectal fat, nodes, and lymphatic vessels to form a distinct anatomic unit: the MESORECTUM (Figure 4).

Mesorectum is surrounded by the MESORECTAL FASCIA (MRF). The virtual space between the MRF and the parietal fascias (PF) is the “holy plane” that constitutes the theoretical surgical circumferential resection margin (CRM) for TME or taTME. Caudally, the MRF is in continuity with the intersphicteric plane. Cranially, it is in continuity with the peritoneal reflection.

MRF status is one of the most important risk factors for recurrence. A positive MRI-assessed margin between the tumor and MRF is defined as tumor lying within 1 mm of the MRF (Figures 5-7).

b) Mesorectal and pelvic fascias

-The MRF is a hypointense line on T2-weighted MR images. However, it is a multi-layered envelope that presents with gaps, and at some points it may not be visible on imaging (Figure 8). It is juxtaposed to the parietal fascias, which have different names according to location. Anteriorly, from the pelvic floor to the peritoneal reflection (PR) is the Dennonvillier fascia (DF) or rectovaginal septum; posteriorly, covering the sacrum, is the presacral fascia (PF). The PF continues anteriorly as the pelvic parietal fascia (PPF).

-The presacral fascia (PSF) lines the anterior aspect of the sacrum, enclosing the sacral vessels. The retrorectal space is located between the posterior MRF and the PSF. The rectosacral fascia (Waldeyer's fascia) divides it into superior and inferior compartment. This fascia originates from the parietal presacral fascia at the level of S2-S4 and passes caudally to reach the rectum at 3 cm to 5 cm above anorectal junction (Figure 9). The presence of lymph nodes in these spaces should be noted, and it should be borne in mind that the vessels in the presacral space may be the source of bleeding during surgery.

c) Peritoneal reflection

The peritoneal reflection (PR) separates the intra- and extraperitoneal portions of the rectum and is a well-defined anatomical landmark at laparotomy (Figure 10-11). The location of a tumor above or below the peritoneal reflection has staging, surgical and treatment implications.

3. DIFFERENTIATING TUMOURS OF THE LOWER RECTUM AND ANAL CANAL

The anal canal length varies from 2-5 cm. A significant anatomical landmark of the anal canal is the DENTATE LINE, which lies 2.5–3 cm proximal to the anal verge and is not visible on MRI (Figure 12).

The UPPER BORDER OF THE PUBORECTALIS sling forms the upper edge of the SURGICAL anal canal. Evaluation of the relationship of the tumor to the upper margin of the puborectalis sling assists in the presurgical determination of whether sphincter-sparing resection is feasible (Figure 12-13).

Staging of tumors in the anal canal must correspond with the histology of the tumor: “Rectal cancer” (adenocarcinoma) and “anal cancer” (squamous cell carcinoma) use different staging systems.

4. T-STAGING: DETAILS THAT MAKE A DIFFERENCE

a) T1 vs T2

MRI and Endoscopic US (eUS) tend to overstage early rectal tumors. The degree of preservation of the submucosal layer seen on MRI as a hyperintense plane between the tumor and the muscularis propria (hypointense) should be assessed to recognize early tumors (Figure 14). Submucosal enhancing stripe status in contrast-enhanced MRI can serve as an independent predictor in the differentiation of stage T1 or lower rectal tumors from stage T2 tumors.

b) T3 category of the TNM

T3 category includes tumors with very different prognoses. Subdivision of T3a/b and T3c/d improves prognostic accuracy (Figure 15).

Differentiating T2 tumors from early T3 tumors can be difficult. A spiculated desmoplastic reaction in the perirectal fat or peritumoral inflammation may mimic tumor involvement. However, T2 and early T3 have the same prognosis (Figure 16).

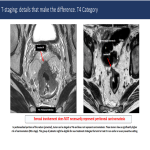

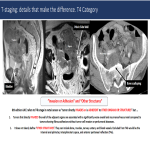

c) T4 category of the TNM

In peritonealized portions of the rectum (proximal), the tumor can be staged as T4a and does not represent carcinomatosis (Figure 17).

8th edition AJCC refers to T4b stage in rectal cancer as “tumor directly invades or is adherent to other organs or structures”. It does not clearly define “OTHER STRUCTURES”. They can include bones, muscles, nerves, ureters, and blood vessels. Excluded from T4b would be the internal anal sphincter, intersphincteric space, and anterior peritoneal reflection (T4a) (Figure 18).

5. LYMPH-NODE: ARE THEY MALIGNANT?

a) Malignant characteristics (Figure 19-20)

b) Location: N or M?

Mesorectal lymph nodes will be removed at surgery. However, extramesorectal LNs are not part of a TME resection, and their location determines whether they are locoregional or metastatic LNs. Locoregional LNs include: sigmoid mesenteric, inferior mesenteric, lateral sacral, presacral, internal iliac and superior/middle/inferior rectal (figure 21).

6. WHY LOOK AT THE RECTAL VASCULATURE?

a) Anatomy: surgical implications

In rectal cancer surgery, surgeons have to ligate the inferior mesenteric artery, they can opt for a high or low ligation (preserving the left colic artery). A good description of the vascular anatomy brings safety to the surgery and can help the surgeon in his decision-making (Figure 22).

b) EMVI or LVI

It is not only extramural VENOUS invasion (EMVI), in pathology, it is LYMPHOVASCULAR INVASION (LVI) (Figure 23-24).

c) Lymph nodes, tumor deposits or lymphovascular invasion

Tumor deposits (TD) are soft-tissue extranodal deposits discontinuous with the primary tumor, as opposed to EMVI which are usually in continuity with the tumor. However, in general, it is not clinically relevant: they should be treated the same (Figure 25).

7. RECOGNISING MUCINOUS TUMORS

The mucinous tumor has two distinct histologic subtypes: mucinous adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma. They are associated with young age, advanced tumor stage at presentation, higher rates of metastases, multiple metastatic sites, and a lower response to chemoradiotherapy.

Mucinous tumors are defined histologically as those containing 50% or more of stromal mucin. They have a worse prognosis than similarly T-staged non-mucinous tumors.

It is incorrect to call a tumor that secretes a large amount of mucin into the lumen, “mucinous” (Figure 26).

Mucinous tumors tipically show large areas of low attenuation and intratumoral calcification on CT and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images due to the presence of mucin pools. High signal intensity is defined as intensity similar to or brighter than the mesorectal fat. T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression, the DWI b0 or a dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) series are helpful for diagnosis (Figure 27).

8. POSTNEOADJUVANT RESTAGING

Tumor response can be heterogeneous even within the same tumor.

There are three main patterns of tumor response: shrinkage, fragmentation and mucin production (Figure 28).

Tumor response does not always results in downstaging.

Different tumor regression grading (TRG) systems have been proposed with measure different things, but have limitations (Figure 29). DIFFUSION-WEIGHTED Imaging (DWI) improves MRI tumor response assessment (Figure 30).