BAV disease is the most common congenital anomaly of the human heart with a prevalence between 1% and 2% with a male preponderance.

It is thought that the true incidence of BAV in the general population may be underestimated.

The reported prevalence of BAV-related aortic dilatation ranges from 33%-80%.

It is worth noting that aortic root dilatation is an important predictor of dissection and rupture in BAV-associated aneurysms,

even if the aortic valve is normally functioning.

•What to look for: When BAV is present,

always check for aortic dilatation•BAV is composed of two leaflets,

of which one is usually larger.

The most common form has the two commissures located in an anteroposterior direction giving left and right cusps.

Type 1 BAVs are more likely to stenose as adults while type 2 will have complications earlier.

A raphe is present on the right and anterior cusps respectively,

and this can make the valve appear tricuspid on echocardiography.

•What to look for: Report the type of BAV

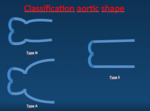

Three basic aortic shapes are defined:

–Type N (“normal” shape).

The diameter of the sinus of Valsalva (Dsinus) is greater than the diameter at the sinotubular juction (DST) and greater than or equal to the diameter of the ascending aorta (Dasc).

–Type A (ascending distension),

where Dsinus is greater than DST but is less than Dasc

–Type E (“effaced”),

where Dsinus is less or equal to DST ,

regardless of Dasc

–

The most prevalent aortic anatomy was shape N.

Shape A is less common and mainly seen in subjects with type 2 BAV.

Shape E was the least common.

•What to look for: report for aortic shape

Major complications are aortic stenosis,

aortic regurgitation,

and endocarditis.

Due to abnormal stresses,

even a normally functioning BAV can progress and damage gradually with more turbulent flow,

as well as restricted motion.

Natural history if BAV ranges from severe aortic stenosis in childhood to longstanding asymptomatic disease into the elderly years.

Aortic stenosis is the most common complication and may require surgery most often necessary in the middle age.

Only 15% of patients with BAV will have a normally functioning in the fifth decade. Aortic regurgitation may present with or without aortic stenosis.

Various etiologies have been suggested to explain the mechanism of aortic regurgitation in BAV,

including: cusp prolapse,

endocarditis,

dilated aortic root and myxoid degeneration of the valve.

Endocarditis is more common in BAV than in the normal tricuspid aortic valve.

The incidence is estimated to be less than 2% in different series,

but the outcome of endocarditis tends to be worse than in normal valves.

•What to look for: Complications are usually depicted by echocardiography.

Nevertheless,

MDCT and cardiac MR are better for planning surgery.

The other major abnormality found in conjunction with BAV disease is coarctation of the aorta.

This occurs in at least 20% of cases and perhaps up to 85%. Less common associated congenital anomalies with BAV include: ventricular septal defects,

Ebstein’s anomaly,

hypoplastic left heart syndrome,

abnormal coronary anatomy,

patent ductus arteriosus,

atrial septal defects and bicuspid pulmonary valve.

•What to look for: Always check for coarctation.

There is a heritable component to BAV disease. There is around a 10% chance of a first degree relative having a bicuspid aortic valve.

Mutations in a gene called NOTCH1 and mutations in chromosomes 18q,

5q and 13q have been found.

Guidance from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommends that all patients with a 1st degree relative with BAV should be evaluated for BAV and aortopathy

•What to look for: When unknown aortic dilatation is present,

check for BAV: it is importante screening for relatives.