Ecocardiography (Fig 4-7).

The mainstay of diagnosis is echocardiography (transthoracic or transesophageal).

Nevertheless,

due to the natural history of BAV to lead to heavily calcified stenotic calves,

the utility of echocardiography can be limited. The parasternal short axis view allows for direct visualization of the valve cusps.

The normal triangular opening shape is lost,

becoming more “fish mouth” like in appearance (usually in systole). Echocardiography can identify other cardiac abnormalities including vegetations,

systolic disfunction,

and visualisation of part of the aortic root (generally the first 3-4 cm).

It is not able however to fully quantify the extent of any aortopathy (whether proximal or distal). Because of these 2 main limitations,

cardiac MRI and CT have been used to augment the diagnostic process.

Cardiac MRI (Fig 8-14).

Cardiac MRI will enable views of the valve to be obtained without interference from calcification and it also allows for excellent assessment of the aorta.

Malaisrie et al found that up to 10% of the patients can be misidentified as having a tricuspid valve using transthoracic echo and 28% had a nondiagnostic study in comparison to 4% and 2% respectively using cardiac MRI.

•What to look for: Cardiac MRI is frequently ordered to clarify a non-diagnostic echocardiography

Calcification could be an important limitation when assess BAV by echocardiography.

Cardiac MRI allows either functional assessment of the BAV and visualization of entire aorta in cases of coarctation.

4D flow MR imaging allows for evaluation of multidirectional blood flow velocity data in the thoracic aorta. It is enable to characterize abnormal secondary blood flow patterns.

4D flow has been used to uncover abnormal helical and vortical-type flow in dilated ascending thoracic aorta.

Patients with abnormal eccentric flow jets in the ascending aorta may be at more risk for development of aneurysm. There are ongoing research projects to quantify the parietal wall stress and identify patients with greater risk for aortic complications.

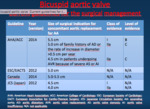

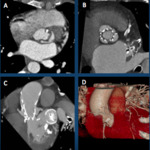

Surgery (Fig 15-23).

Aortic valve repair o replacement: indicated in patients with severe aortic stenosis or aortic insufficiency/regurgitaton,

in those patients having symptoms,

and/or those with evidence of abnormal left ventricular function.

In selected cases,

it is possible to perform a minimally-invasive aortic valve replacement: Aortic valve replacement through a smaller “keyhole” incision

•Modified Bentall procedure: Replacement of the entire aortic root including the aortic valve and abnormal aortic wall

•David procedure: Valve-sparing aortic root replacement (aortic root replacement where one´s own aortic valve is spared but the abnormal aortic wall is replaced

•Repair of the aorta: the diseased portion of aorta is removed and replaced with a synthetic (man-made) graft

•Endovascular therapy.

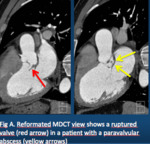

MDCT plays an important role when treatment of difficult cases are considered.

•What to look for: Choose MDCT as imaging technique in difficult cases

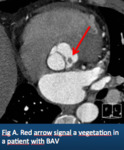

Endocarditis/vegetation is more common in BAV than in the normal tricuspid aortic valve.

The incidence is estimated to be less than 2% in different series,

but the outcome of endocarditis tends to be worse than in normal valves.

Although MDCT usually plays a complementary role to echocardiograpghy,

many times depicts better the anatomy of paravalvular abscess

TAVI must be avoided in BAV with extreme calcifications,

extensive asymmetirc valves,

very elliptic annulus or small distance from leaflets to the coronary ostia.

Currently,

the presence of a BAV might not be considered as an absolute contraindication for TAVI.

•What to look for: when TAVI is planned,

check for distance from leaflets to the coronary ostia and morphology of annulus