THE UMBILICAL VEIN

In adults,

the umbilical vein is usually completely occluded,

mainly in its distal part,

forming the round ligament,

a fibrous structure.

A very thin patent remnant of the umbilical vein may be present in connection with the left branch of the portal vein in normal individuals.

It is called the Baumgarten’s recess [1].

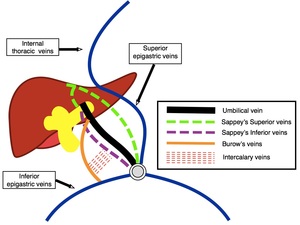

THE PARAUMBILICAL VEINS

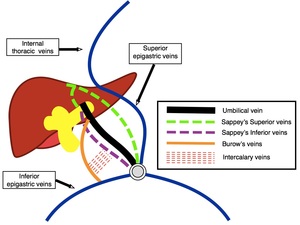

The paraumbilical veins are found around the falciform ligament next to the round ligament.

They are composed by Burow's veins and Sappey's inferior and superior veins [2].

-

Burow’s veins: ascending veins from the inferior epigastric veins alongside the occluded umbilical vein and terminating in the middle third of the umbilical vein.

-

Sappey’s superior veins: they drain the median part of the diaphragm,

traverse the upper part of the falciform ligament to reach the liver surface,

and then enter the sublobular divisions of the portal Veins.

-

Suppey’s inferior veins: they traverse the inferior part of the falciform ligament to enter the liver and communicate with the portal system in a variety of ways [2].

Although Burow’s veins do not enter the portal system directly,

they communicate with Sappey’s inferior veins through the intercalary veins.

For this reason,

they can also become dilated in cases of portal hypertension and in other clinical conditions.

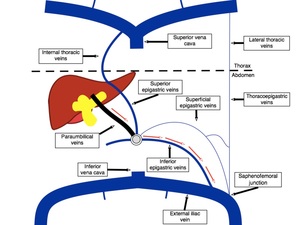

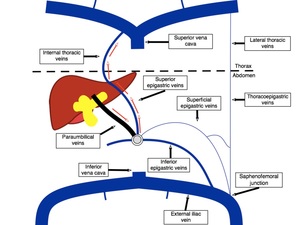

Fig. 1: Simplified scheme demonstrating the umbilical vein and the paraumbilical veins.

References: José Claudio Nogueira Junqueira, 2018.

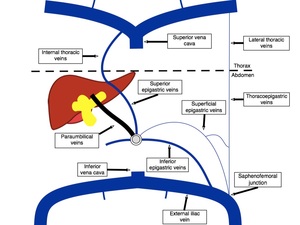

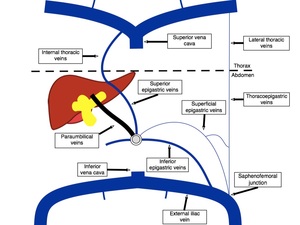

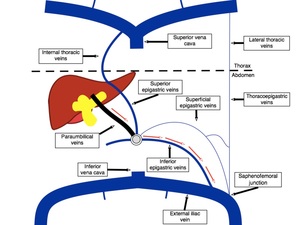

The paraumbilical veins connect the left branch of the portal vein with veins of the ventral abdominal wall inferiorly,

posterior to the rectus sheath,

in the extraperitoneal fat space,

at the umbilical region.

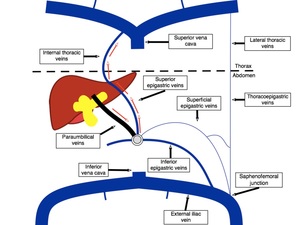

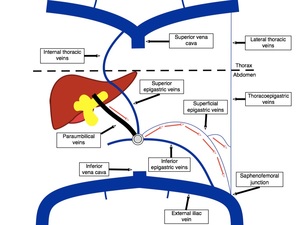

Fig. 2: Simplified scheme demonstrating the paraumbilical veins and their main venous connections.

References: José Claudio Nogueira Junqueira, 2018.

Different types of communication between them and the systemic circulation have been described [3-4]:

-

Through deep inferior epigastric veins to reach the external iliac veins.

-

Through deep superior epigastric veins to reach the internal thoracic veins.

-

Through superficial epigastric veins to reach the saphenous veins.

The most common type is the connection with the inferior epigastric veins.

A combination of these pathways may be present in the same patient.

It also can be bilateral or unilateral.

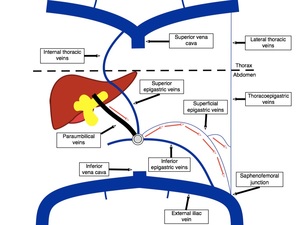

Fig. 3: Simplified scheme demonstrating hepatofugal flow through the paraumbilical veins towards the inferior epigastric veins in portal hypertension.

References: José Claudio Nogueira Junqueira, 2018.

Fig. 4: Simplified scheme demonstrating hepatofugal flow through the paraumbilical veins towards the superior epigastric veins in portal hypertension.

References: José Claudio Nogueira Junqueira, 2018.

Fig. 5: Simplified scheme demonstrating hepatofugal flow through the paraumbilical veins towards the superficial epigastric veins in portal hypertension.

References: José Claudio Nogueira Junqueira, 2018.

IMPORTANCE OF THE PARAUMBILICAL VEINS

In normal individuals,

the paraumbilical veins are usually collapsed,

but patent.

They do not have any relevant clinical function and,

because they are very thin,

they may not be identified unless high resolution imaging methods are used.

In certain clinical conditions,

they can become dilated and allow blood flow between the portal system and the systemic circulation.

Since the paraumbilical veins are not occluded,

even in the normal individual,

it is more suitable to use the term enlargement or engorgement of the paraumbilical veins whenever they are found during ultrasound examination,

rather than the term "recanalization" used by some.

Most often,

they work as a portosystemic shunt due to portal hypertension.

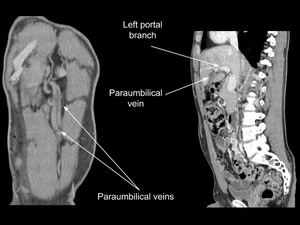

Rarely,

the paraumbilical veins allow venous flow from the systemic circulation towards the portal system,

in an hepatopetal direction.

These unusual pathways are more commonly related to inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis [5].

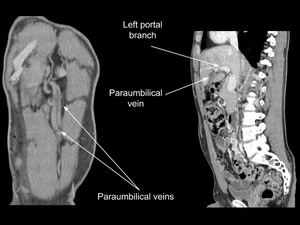

Fig. 6: Coronal and sagittal multiplanar reformation (MPR) images from enhanced abdominal CT showing patent paraumbilical veins and their communication with the left branch of the portal vein in a patient with extensive inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

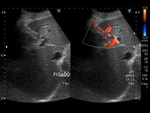

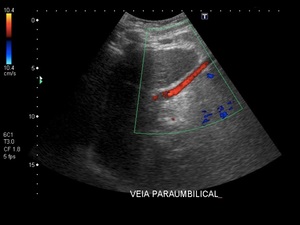

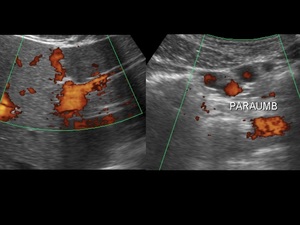

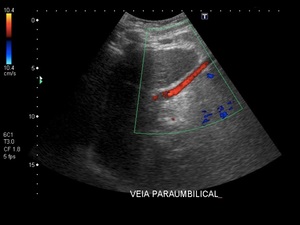

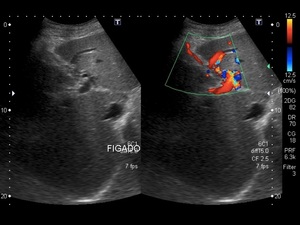

Fig. 7: Ultrasound Doppler image of a typical patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow in a cirrhotic patient.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

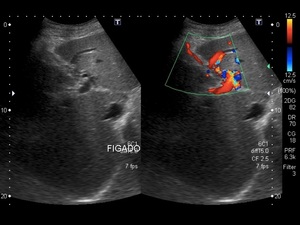

Fig. 8: Ultrasound Doppler image of a typical patent paraumbilical vein with hepatofugal flow in a cirrhotic patient.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

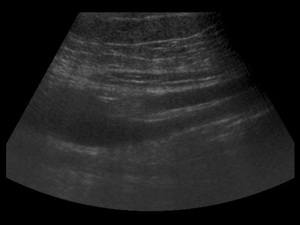

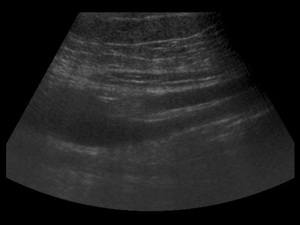

Fig. 9: Ultrasound image of two paraumbilical veins posterior to the rectus sheath (longitudinal axis).

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

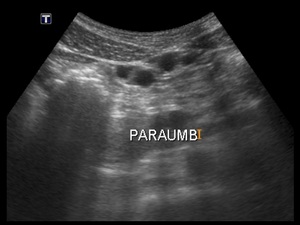

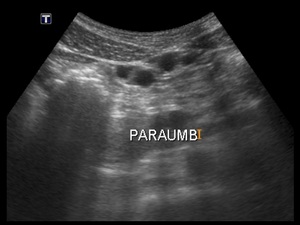

Fig. 10: Ultrasound image of two paraumbilical veins posterior to the rectus sheath (transverse axis). Because of their tortuosity, they simulate the existence of four veins.

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.

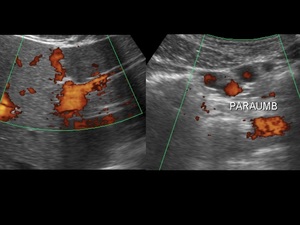

Fig. 11: Ultrasound Power Doppler image of paraumbilical veins with their connection with the left branch of the portal vein (image on the left) and transverse image of two paraumbilical veins posterior to the rectus sheath, simulating the existence of four veins, because of their tortuosity (images on the right).

References: Institute of Radiology (InRAD), Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (USP)/ Brazil 2018.